Ever since the poetry, short stories, and writings of Henry Dumas, a specter has risen from the outer fringes of American art and literature—Afro-Surrealism. A hallmark of this genre is the reader’s, author’s, and fictional characters’ self-awareness that the world they live in is out of whack. The term has roots in surrealism, defined as humor based on detours of logic. winning time blurs fact and fiction by existing on the knife edge between the two, and recently to controversy. As a show about one of the largest and most used Bmissing teams in NBA history, winning time had the chance to get into the canon of works on the complexity of Black of identity recently made by shows like Mainstream subway, Atlanta, the visual work of Kara Walker and the films of Jordan Peele. There are shades of surrealism in the latest HBO series — characters speak directly to the audience, animated sequences burst out once per episode, and over-the-top graphics punctuate almost every scene. While the show clearly has a surrealist kick stylistically, it lacks an Afrocentric perspective.

winning time turns sharpest into left field with white characters behind the steering wheel. In the first season, it was John C. Reilly’s Jerry Buss in particular who broke most of the fourth walls and engaged us, the audience, in the conversation. That’s not to say Buss has nothing to say. His make-or-break gamble set the Lakers on the path to their era. But we’ve walked this path before. There’s no need to fill a woke quota by focusing the show on fictional marginalized characters. We get enough of that from commercials for Adidas and Gillette.

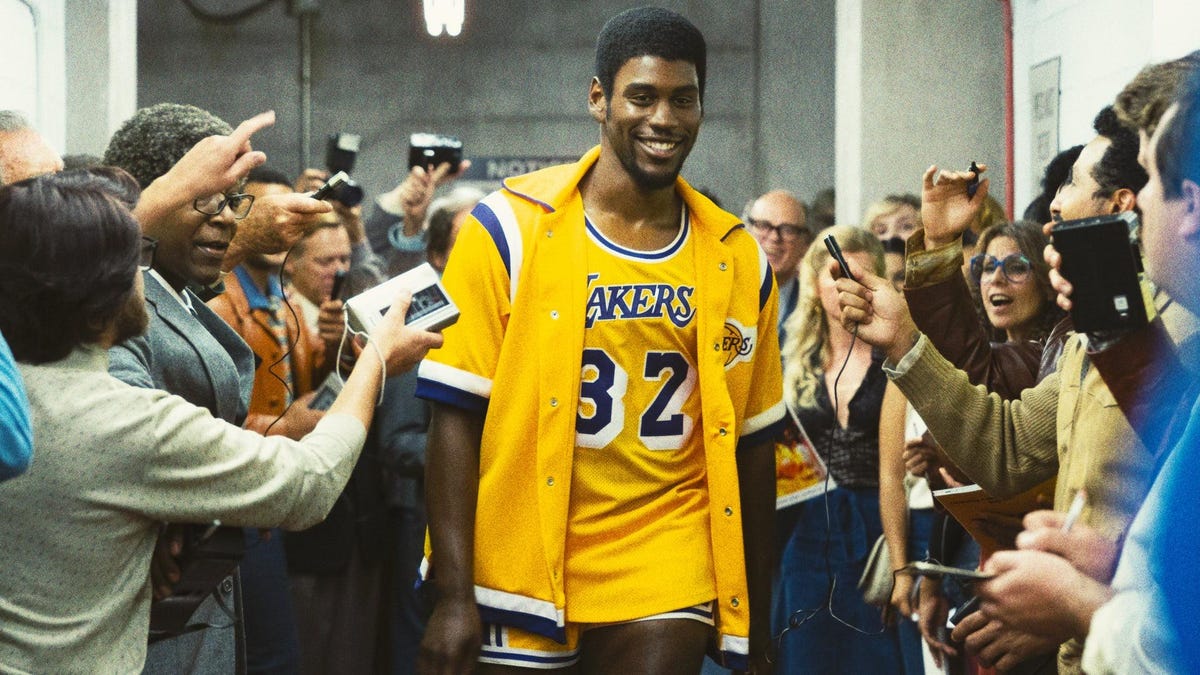

The shame behind this missed opportunity is that the show could have allowed Magic and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to be the avatars for the show’s foray into surrealism. It would have been a more exciting narrative to see and hear what they were thinking as those playing the game on the pitch while controlling the political game off the pitch. But unfortunately, these moments are few and far between. The world this BLack of people borders on the absurd. Magic, in particular, constantly feels out of place and forced to compete with other Bmissing stars and especially his white rookie counterpart Larry Bird. Magic’s working-class roots are constantly used as a source of difference. The NBA is a white man’s game, and the Lakers players are involuntary pawns. Still, they must navigate the ins and outs of their lives as if everything meant something, a hallmark of surrealism. But no matter how absurd situational moments are winning time could be, the very real racism, and fame lurks around every corner for his Bcharacters are missing.

In the introduction to Episode 8, “California Dreaming,” Buss gains the ubiquitous ability to walk through frozen time and tells a parable about not giving up through the story of Englishman Roger Bannister, who breaks the world record for running the mile. Buss does this while walking through Staples Stadium, where players and fans are frozen in time. The tale of Banister’s history-making performance is a curious tale for these brave Lakers who want to make history. So why not let Magic tell the story? Reilly has received critical acclaim as the lead actor of the series and is the Shakespearean character of this story, but perhaps that was a creative error. With all the controversy surrounding the show’s accuracy in terms of its core cast, it would have been a more exciting risk to have Magic tell this story from its point of view.

Think of the perspective — a poor, working-class African American man plucked from his humble Michigan upbringing to be the missing piece of a Los Angeles fairy tale. It would have re-centered the show around Magic’s POV perspective, casual and without the neoliberal virtue signal. The show did a great job of drawing each character in grayscale and showing the qualities that made them heroes of the NBA and villains in their own right. It could have been so much more. That’s not to say that Reilly as Buss isn’t compelling. His three-pronged relationship in this episode with his disappointed daughter, dying mother and her nurse is a hallmark of the series. A late-night car scene between Reilly and his mother’s nurse (Natalia Cordova-Buckley) walks the line between tender and horny and shows how deep his Oedipus complex runs. After soaking her shirt with his tearful breakdown over his mother’s impending death, he unbuttons the nurse’s top to suck on her teat.

G/O Media may receive a commission

39% discount

Toloco massage gun

Relax!

Has four different speeds, ten different heads for different body parts and is super easy to use thanks to an LED display and its light weight.

We get brief moments where Magic takes over the narrative reins, such as when he bitches into the camera about not getting support from his teammates as an All-Star. But they are brief and not nearly as majestic or long as Buss’s soliloquies. Magic is too interesting for one person, both the real version and this simulation, to be marginalized. And that’s Winning Time’s biggest flaw, which gives its most personal and introspective moments to Buss while he spreads the crumbs among the rest of the extended cast. To be fair, how many of us can relate to the multi-million dollar Playboy Buss shenanigans? It’s Magic’s tragic arc, based on everyday good versus evil, that feels more familiar.

At the end of the day, isn’t the NBA a star-driven league anyway?